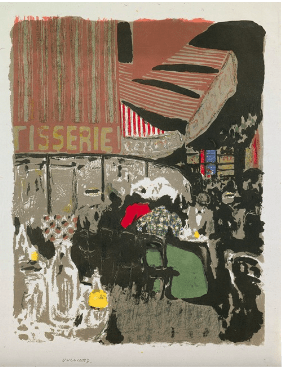

Visito a una artista en Berlin que me muestra una de sus maximas referencias en pintura que es el pintor Edouard Vuillard. Me interesa su arte por mis estudios acerca del expresionismo, esta vez el Frances.

Vuillard belonged to a quasi-mystical group of young artists that arose in about 1890 and called themselves the Nabi, a Hebrew word for prophet. The Nabi rejected impressionism and considered simple transcription of the appearance of the natural world unthinking and unartistic. Inspired by Gauguin’s work and symbolist poetry, their paintings evoke rather than specify, suggest rather than describe. Recognizing that the physical components of painting — colored pigments arranged on a flat surface — were artificial, they considered as false the traditional convention of regarding paintings as re-creations of the natural world.

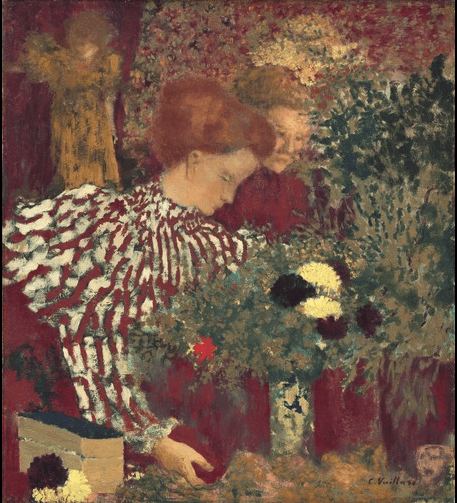

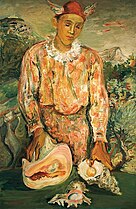

Woman in a Striped Dress is one of five decorations Vuillard painted in 1895 for Thadée Natanson, publisher of the avant-garde journal La Revue Blanche, and his wife Misia Godebska, an accomplished pianist. The five, which differ in size and orientation, are intimate, self contained interiors, Vuillard’s principal subject. All display rich harmonies in a restricted range of color and densely arranged in intricate patterns. The introspective woman arranging flowers here perhaps represents the red-haired Misia, whom Vuillard admired greatly. Vuillard adopted the symbolist idea of synesthesia, whereby one sense can evoke another, and in Woman in a Striped Dress the sumptuous visual qualities of Vuillard’s reds may suggest the lush chords of music that Misia performed.

Jean-Édouard Vuillard was a French painter, decorative artist and printmaker. From 1891 through 1900, he was a prominent member of the Nabis, making paintings which assembled areas of pure color, and interior scenes, influenced by Japanese prints, where the subjects were blended into colors and patterns. He also was a decorative artist, painting theater sets, panels for interior decoration, and designing plates and stained glass. After 1900, when the Nabis broke up, he adopted a more realistic style, painting landscapes and interiors with lavish detail and vivid colors. In the 1920s and 1930s he painted portraits of prominent figures in French industry and the arts in their familiar settings.

Vuillard was influenced by Paul Gauguin, among other post-impressionist painters.

Jean-Édouard Vuillard was born on 11 November 1868 in Cuiseaux (Saône-et-Loire), where he spent his youth. Vuillard’s father was a retired captain of the naval infantry, who after leaving the military became a tax collector. His father was 27 years older than his mother, Marie Vuillard (née Michaud), who was a seamstress.

In 1877, after his father’s retirement, the family settled in Paris at 18 rue de Chabrol, then moved to Rue Daunou, in a building where his mother had a sewing workshop. Vuillard entered a school run by the Marist Brothers. He was awarded a scholarship to attend the prestigious Lycée Fontaine, which in 1883 became the Lycée Condorcet. Vuillard studied rhetoric and art, making drawings of works by Michelangelo and classical sculptures. At the Lycée he met several of the future Nabis, including Ker-Xavier Roussel (Vuillard’s future brother in law), Maurice Denis, writer Pierre Véber, and the future actor and theater director Aurélien Lugné-Poe.

In November 1885, when he left the Lycée, he gave up his original idea of following his father in a military career, and set out to become an artist. He joined Roussel at the studio of painter Diogène Maillart, in the former studio of Eugène Delacroix on Place Fürstenberg. There, Roussel and Vuillard learned the rudiments of painting. In 1885 he took courses at the Académie Julian, and frequented the studios of the prominent and fashionable painters William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Robert-Fleury. However, he failed in the competitions to enter the École des Beaux-Arts in February and July 1886 and again in February 1887. In July 1887, the persistent Vuillard was accepted, and was placed in the course of Robert-Fleury, then in 1888 with the academic history painter Jean-Léon Gérôme. In 1888 and 1889, he pursued his studies in academic art. He painted a self-portrait with his friend Waroquoy, and had a crayon portrait of his grandmother accepted for the Salon of 1889. At the end of that academic year, and after a brief period of military service, he set out to become an artist.

Late in 1889 he began to frequent the meetings the informal group of artists known as Les Nabis, or The prophets, a semi-secret, semi-mystical club which included Maurice Denis and some of his other friends from the Lycée. In 1888 the young painter Paul Sérusier had traveled to Brittany, where, under the direction of Paul Gauguin, he had made a nearly abstract painting of the seaport, composed of areas of color. This became The talisman, the first Nabi painting. Serusier and his friend Pierre Bonnard, Maurice Denis and Paul Ranson, were among the first Nabis of nabiim, dedicated to transforming art down to its foundations. In 1890, through Denis, Vuillard became a member of the group, which met in Ransom’s studio or in the cafes of the Passage Brady. The existence of the organization was in theory secret, and members used coded nicknames; Vuillard became the Nabi Zouave, because of his military service.

He first began working on theater decoration. He shared a studio at 28 Rue Pigalle with Bonnard with the theater impresario Lugné-Poe, and the theater critic Georges Rousel. He designed sets for several works by Maeterlinck and other symbolist writers. In 1891 he took part in his first exposition with the Nabis at the Chateau of Saint-Germain-en-Laye. He showed two paintings, including The Woman in a Striped Dress (see gallery below). The reviews were largely good, but the critic of Le Chat Noir wrote of “Works still indecisive, where one finds the features in style, literary shadows, sometimes a tender harmony.” (September 19, 1891).

Vuillard began keeping a journal during this time, which records the formation of his artistic philosophy. “We perceive nature through the senses which give us images of forms, sounds, colors, etc.” he wrote on 22 November 1888, shortly before he became a Nabi. “A form or a color exists only in relation to another. Form does not exist on its own. We can only conceive of the relations.” In 1890 he returned to the same idea: “Let’s look at a painting as a set of relations that are definitely detached from any idea of naturalism.”

The works of Vuillard and the Nabis were strongly influenced by Japanese woodblock prints, which were shown in Paris at the gallery of art dealer Siegfried Bing, and at a large show at the École des Beaux Arts in 1890. Vuillard himself acquired a personal collection of one hundred eighty prints, some of which are visible in the backgrounds of his paintings. The Japanese influence appeared particularly in his work in the negation of depth, the simplicity of forms, and strongly contrasting colors. The faces were often turned away, and drawn with just a few lines. There was no attempt to create perspective. Vegetal, floral and geometric designs in the wallpaper or clothing were more important than the faces. In some of Vuillard’s works, the persons in the paintings almost entirely disappeared into the designs of the wallpaper. The Japanese influence continued in his later, post-Nabi works, particularly in the painted screens depicting Place Vintimille he made for Marguerite Chaplin.

Another aspect of the Nabi philosophy shared by Vuillard was the idea that decorative art had equal value with traditional easel painting. Vuillard created theatrical sets and programs, decorative murals and painted screens, prints, designs for stained glass windows, and ceramic plates. In the early 1890s, he worked especially for the Théâtre de l’Œuvre of Lugné-Poe designing backdrops and programs.

From theater decoration, Vuillard soon moved into interior decoration. In the course of his theater work, met brothers Alexandre and Thadée Natanson, the founders of La Revue Blanche, a cultural review. Vuillardʹs graphics appeared in the journal, together with Pierre Bonnard, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Félix Vallotton and others. In 1892, on a commission Natanson brothers, Vuillard painted his first decorations (“apartment frescoes”) for the house of Mme Desmarais. He made others in 1894 for Alexandre Natanson, and in 1898 for Claude Anet.

He used some of the same techniques he had used in the theater for making scenery, such as peinture à la colle, or distemper, which allowed him to make large panels more quickly. This method, originally used in Renaissance frescos, involved using rabbit-skin glue as a binder mixed with chalk and white pigment to make gesso, a smooth coating applied to wood panels or canvas, on which the painting was made. This allowed the painter to achieve finer detail and color than on canvas, and was waterproof. In 1892 he received his first decorative commission to make six paintings to be placed above the doorways of the salon of the family of Paul Desmarais. He designed his panels and murals to fit into the architectural setting and the interests of the client.

In 1894, he and the other Nabis received a commission from art gallery owner Siegfried Bing, who had given Art Nouveau its name, to design stained glass windows to be made by the American firm of Louis Tiffany. Their designs were displayed in 1895 at the Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts, but the actual windows were never made. In 1895 he designed a series of decorative porcelain plates, decorated with faces and figures of women in modern dress, immersed in floral designs. The plates, along with his design for the Tiffany window and the decorative panels made for the Natansons, were displayed at the opening of Bing’s gallery Maison de l’Art Nouveau in December 1895.

Some of his best-known works, including the Les Jardins Publiques (The Public Gardens) and Figures dans un Interieur (Figures in an Interior) were made for the Natanson brothers, whom he had known at the Lycée Condorcet, and for their friends. They gave Vuillard freedom to choose the subjects and style. Between 1892 and 1899, Vuillard made eight cycles of decorative paintings, with altogether some thirty panels. The murals, though rarely displayed during his lifetime, later became among his most famous works.

Public Gardens is a series of six panels illustrating children in the parks of Paris. The patrons, Alexander Natanson and his wife Olga, had three young daughters. The paintings show a variety of different inspirations, including the medieval tapestries at the Hotel de Cluny in Paris that Vuillard greatly appreciated. For this series Vuillard did not use oil paint, but peinture a la colle, a method he had used in painting theater sets, which required him to work very quickly, but allowed him to make modifications and to achieve the appearance of frescoes. He received the commission on 24 August 1894, and completed the series at the end of the same year. They were installed in the dining room/salon of the Natansons.

Vuillard frequently painted interior scenes, usually of women in a workplace, at home, or in a garden. The women’s faces and features are rarely the center of attention; the painting were dominated by the bold patterns of the costumes, the wallpaper, carpets, and furnishings.

He painted a series of paintings of seamstresses in the workshop of a dressmaker, based on the workshop of his mother. In La Robe à Ramages (The flowered dress; 1891), the women in the workshop are assembled out of areas of color. The faces, seen from the side, have no details. The patterns of their costumes and the decor dominate the pictures. The figures include his grandmother, to the left, and his sister Marie, in the bold patterned dress which is the central feature of the painting. He also placed a mirror on the wall to the left, scene, a device which allowed him to two points of view simultaneously and to reflect and distort the scene. The result is a work that is deliberately flattened and decorative.

The Seamstress with Chiffons (1893) also presents a seamstress at work, seated in front of a window. Her face is obscure and the image appears almost flat, dominated by the floral patterns of the wall.

In 1895 Vuillard received a commission from the cardiologist Henri Vaquez for four panels to decorate the library of his Paris house at 27 rue du Général Foy. The primary subjects were women engaged in playing the piano, sewing, and other solitary occupations in a highly decorated bourgeois apartment. The one man in the series, presumably Vaquez himself, is shown in his library reading, paying little attention to the woman sewing next to him. The tones are somber ochres and purples. The figures in the panels are almost entirely integrated the elaborate wallpaper, carpet, and patterns of the dresses of the women. Art critics immediately compared the works to medieval tapestries. The paintings, completed in 1896, were originally titled simply People in Interiors but later critics added subtitles: Music, Work, The Choice of Books, and Intimacy. They are now in the Museum of the Petit Palais in Paris.

In 1897 his interiors showed a noticeable change, with Large Interior with Six Persons. The picture was much more complex in its perspective, depth and color, with carpets arranged in different angles, and the figures scattered around the room more recognizable. It was also complex in its subject matter. The setting appears to be the apartment of the Nabi painter Paul Ranson, reading a book; Madame Vuillard seated in an armchair, Ida Rousseau coming in the door, and her daughter Germaine Rousseau, standing at the left. The unstated subject was the romantic affair between Ker-Xavier Roussel and Germaine Rousseau, his sister-in-law, which shocked the Nabis.

The Nabis went their separate ways after their exposition in 1900. They had always had different styles, though they shared common ideas and ideals about art. The separation was made deeper by the Dreyfus Affair (1894–1908), which split French society. Dreyfus was a Jewish French army officer accused falsely of treason, and sentenced to a penal colony, before finally being exonerated. Among the Nabis, Vuillard and Bonnard supported Dreyfus, while Maurice Denis and Sérusier supported the side of the French army.

After the separation of the Nabis in 1900, the style and subjects of Vuillard changed. He had formerly been, with the Nabis, in the vanguard of the avant-garde. Now he gradually abandoned the close, crowded and dark interiors he had painted before 1900, and began to paint more outdoors, with natural light. He continued to paint interiors, but the interiors had more light and color, more depth, and the faces and features were clearer. The effects of the light became primary components of his paintings, whether they were interior scenes or the parks and streets of Paris. He gradually returned to naturalism. He held his second large personal exhibition at the Gallerie Bernheim-Jeune in November 1908, where he presented many of his new landscapes. He was praised by one anti-modernist critic for “his delicious protest against systematic deformations.”

In 1912, Vuillard, Bonnard and Roussel were nominated for the Légion d’honneur, but all three refused the honor. “I do not seek any other compensation for my efforts than the esteem of people with taste,” he told a journalist.

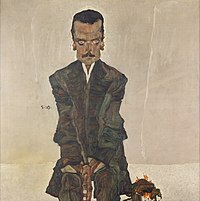

In 1912, Vuillard painted Théodore Duret in his Study, a commissioned portrait that signaled a new phase in Vuillard’s work, which was dominated by portraiture from 1920 onwards.

Vuillard served as a juror with Florence Meyer Blumenthal in awarding the Prix Blumenthal, a grant given between 1919–1954 to young French painters, sculptors, decorators, engravers, writers, and musicians.

After 1900 Vuillard continued to paint numerous domestic interiors and gardens, but in a more naturalistic, colorful style than he had used as a Nabi. Though the faces of the persons were still often looking away, the interiors had depth, a richness of detail, and warmer colors. He particularly captured the play of the sunlight on the gardens and his subjects. He did not want to return to the past, but wanted to move into the future with a vision that was more decorative, naturalistic and familiar than that of the modernists.

He made new series of decorative panels, depicting urban scenes and parks in Paris, as well as many interior scenes of Paris shops and homes. He depicted the galleries of the Louvre Museum and the Museum of Decorative Arts, the chapel of the Palace of Versailles.

The theater was an important part of Vuillard’s life. He had begun as a Nabi by making sets and designing programs for an avant-garde theater, and throughout his life had close contacts with theater people. He was a friend of, and painted the actor and director Sacha Guitry. In May 1912, he received an important commission for seven panels, and three paintings above the doorways, for the new Théâtre des Champs-Élysées in Paris, including one of Guitry in his loge at the theater, and another of the comic playwright Georges Feydeau. He attended the performances of the Ballets Russes between 1911 and 1914, and dined with the Russian director of the Ballet, Sergei Diaghilev, and with the American dancer Isadora Duncan. and frequented the Follies Bergere and the Moulin Rouge in their heyday. In 1937 he and Bonnard received combined his impressions of the history of Paris theater world in a large mural, La Comédie, for the foyer of the new Théâtre national de Chaillot, built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition.

Following the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914, Vuillard was briefly mobilized for military duty as a highway guard. He was soon released from this duty, and returned to painting. He visited the armaments factory of his patron, Thadée Natanson, near Lyon, and later made a series of three paintings of the factories at work. He served briefly, from 2 February to 22 February, as an official artist to the French armies in the region of the Vosges, making a series of pastels. These included a sympathetic sketch of a captured German prisoner being interrogated. In August 1917, back in Paris, he received a commission from the architect Francis Jourdain for a mural for a fashionable Paris café, Le Grand Teddy.

In 1921 he received an important commission for decorative panels for the art patron Camille Bauer, for his residence in Basel, Switzerland. Vuillard completed a series of four panels, plus two over-the-door paintings, which were finished by 1922. He passed his summers each year from 1917 to 1924 at Vaucresson, at a house he rented with his mother. He also made a series of landscape paintings of the area.

After 1920 he was increasingly occupied painting portraits for wealthy and distinguished Parisians. He preferred to use the a la collie sur toiel, or distemper technique, which allowed him to create more precise details and richer color effects. His subjects ranged from the actor and director Sacha Guitry to the fashion designer Jeanne Lanvin, Lanvin’s daughter, the Contesse Marie-Blanche de Polignac, the inventor and aviation pioneer Marcel Kapferer, and the actress Jane Renouardt. He usually presented his subjects in their studios or homes or backstage, with lavishly detailed backgrounds, wallpaper, furnishings and carpets. The backgrounds both created a mood, told a story, and served as a contrast to bring out the main figure.

Between 1930 and 1935 he divided his time between Paris and the Chateau de Clayes, owned by his friend Hessel. He did not receive any official recognition from the French state until July 1936, when he was commissioned to make a mural, La Comédie, depicting his impressions of the history of Paris theater world for the foyer of the new Théâtre national de Chaillot, built for the 1937 Paris International Exposition. In August of the same year, the City of Paris bought four of paintings, Anabatistes, and a collection of sketches. In 1937 he received another major commission, along with Maurice Denis and Roussel, for a monumental mural at the Palace of the League of Nations in Geneva.

In 1938, he received more official recognition. He was elected in February 1938 to the Académie des Beaux Arts, and in July 1938 the Musée des Arts Decoratifs presented a major retrospective of his paintings. Later in the year he traveled to Geneva to oversee the installation of his mural Peace, Protector of the Arts at the League of Nations Building.

In 1940, he completed his last two portraits. He suffered from pulmonary difficulties, and traveled to La Baule in Loire-Atlantique to restore his health. He died there on 21 June 1940, the same month that the French army was defeated by the Germans in the Battle of France.

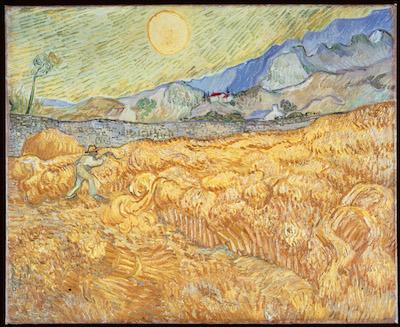

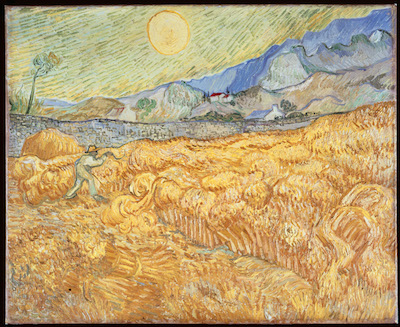

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Reaper (Harvest in Provence) (Champ de blé avec moissonneur), 1889, Museum Folkwang. Photo Credit: bpk, Berlin / Museum Folkwang/ Art Resource, NY

Vincent van Gogh, Wheat Field with Reaper (Harvest in Provence) (Champ de blé avec moissonneur), 1889, Museum Folkwang. Photo Credit: bpk, Berlin / Museum Folkwang/ Art Resource, NY Paul Gauguin, Swineherd, 1888, gift of Lucille Ellis Simon and family in honor of the museum’s 25th anniversary

Paul Gauguin, Swineherd, 1888, gift of Lucille Ellis Simon and family in honor of the museum’s 25th anniversary Paul Gauguin, Haystacks in Brittany (Les Meules / Le champ de pommes de terre), 1890, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.11, image courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.

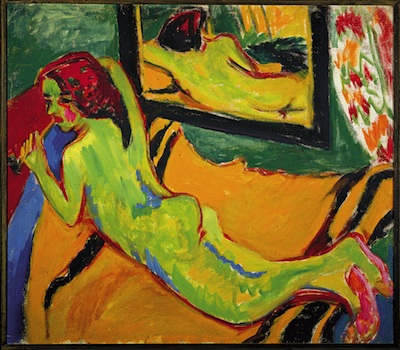

Paul Gauguin, Haystacks in Brittany (Les Meules / Le champ de pommes de terre), 1890, National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., gift of the W. Averell Harriman Foundation in memory of Marie N. Harriman, 1972.9.11, image courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C. Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Reclining Nude in Front of Mirror (Liegender Akt vor Spiegel), 1909–10, Brücke-Museum, Berlin (Inv.-Nr. 31/72), © Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Courtesy Ingeborg & Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern. Photo © Brücke-Museum, Berlin, photographer: Roman März

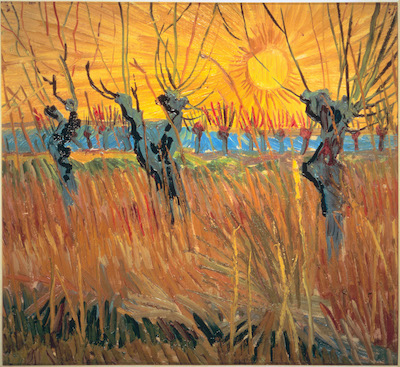

Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Reclining Nude in Front of Mirror (Liegender Akt vor Spiegel), 1909–10, Brücke-Museum, Berlin (Inv.-Nr. 31/72), © Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Courtesy Ingeborg & Dr. Wolfgang Henze-Ketterer, Wichtrach/Bern. Photo © Brücke-Museum, Berlin, photographer: Roman März Vincent van Gogh, Pollard Willows at Sunset, Arles (Saules au coucher du soleil, Arles), 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands, Photo Credit: Art Resource, NY

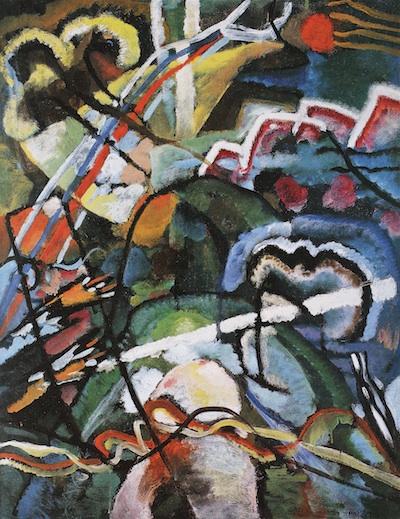

Vincent van Gogh, Pollard Willows at Sunset, Arles (Saules au coucher du soleil, Arles), 1888, Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, The Netherlands, Photo Credit: Art Resource, NY Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch I for Painting with White Border, 1913, Phillips Collection, © 2014 Wassily Kandinsky/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © The Phillips Collection

Wassily Kandinsky, Sketch I for Painting with White Border, 1913, Phillips Collection, © 2014 Wassily Kandinsky/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/ADAGP, Paris, photo © The Phillips Collection Franz Marc, Stony Path (Mountains/Landscape) Steiniger Weg (Gebirge/Landschaft), 1911 (repainted 1912), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Women’s Board and Friends of the Museum, photo © San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Franz Marc, Stony Path (Mountains/Landscape) Steiniger Weg (Gebirge/Landschaft), 1911 (repainted 1912), San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, gift of the Women’s Board and Friends of the Museum, photo © San Francisco Museum of Modern Art

Link: https://ok.ru/video/2924038589018

Link: https://ok.ru/video/2924038589018