Jean-Luc Godard – Famous French film director

https://www.francethisway.com/culture/jean-luc-godard.php#:~:text=Godard%20is%20a%20French%20filmmaker,as%20both%20radical%20and%20stylistic.

Godard is a French filmmaker perhaps best known for his way of challenging Hollywood. One of the most influential members of the Nouvelle Vague or “The French Wave”, he is universally recognized as both radical and stylistic. His work reflected a profound respect and knowledge of film history, but also a very deep understanding of Marxist philosophy.

Godard was born in Paris by French-Swiss parents and was schooled in Switzerland. Later on, when he was at the Sorbonne he studied ethnology and it was at this time he also found his way closer to a group of filmmakers and film theorists who would become the Nouvelle Vague.

It is often said that Godard sought an artistic outlet and to open a discussion about international conflict in his films, such as the Algerian War of Independence which he dealt with in Le Petit Soldat. And, he is often recognized for showing a multifaceted view of this conflict rather than pushing any particular political viewpoint.

But Godard was also very concerned with issues in his contemporary France. An example of this would be Vivre sa Vie, the portrayal of a French prostitute.

His most celebrated time period is maybe 1960-1967. This time period in Paris was not ruled by one very clear movement. Instead Paris experienced flashes of opposing takes on various international conflicts such as colonialism. Godard’s first feature from this time was Breathless, 1960. During this time Godard was very focused on narrative and he often referred to various times/events/films in film history. Another example of this is Week End, 1967.

Following this period, Godard made a sharp u-turn in his work. Instead of the strong narrative focus and celebration of film history his work became more revolutionary, and he started to refer to cinema history as bourgeois (which essentially meant it had no worth).

While Godard’s most famous work was created in the 1960’s, he has continued to make films that move. And, it is possible that he created the most important work of his career as late as in the 1990s. Histoires du Cinema is a celebration of his video work and the issues of history of film.

During his career in film Godard has won 30 significant industry awards and earned 28 nominations. One of his most famous quotes to date is “You don’t make a movie, the movie makes you.

“I work like a painter” – exploring Jean-Luc Godard’s use of artwork in his films

https://hero-magazine.com/article/221890/jean-luc-godard-art

Imagine you employ a bunch of actors, one of them is even an astonishing foreign beauty, you have a camera crew, a gaffer, set designers, prop makers, producers, you even have a composer for the score, you manage to scrape up all that money together to finally make a movie, the first day of shooting is finally here… and then you show up on set without a script. That was Jean-Luc Godard – most famously on the set of his 1963 film, Le petit soldat. Was he going to lose it all and never gain the trust of any producer again? No, instead he would create the most stylised and influential body of work a filmmaker has ever produced.

Godard’s spontaneous way of working meant he would start developing the dialogue and script on the spot. Raw, unpredictable and with typical Parisian intellectualism, he created like a true artist does with his masterpieces; from scratch. He rejected the idea of pre-writing a film early on in his career. ‘Seeing precedes the written word’ was the motto and a focus on visual language led the way – in this sense, he repeatedly emphasised the parallels between the history of cinema with the history of painting.

Art is ever-present in Godard’s work; graphic design and modern art are skilfully interpreted and used as props, drawing as much from pop culture as art classique to create a unique collage style. The run through the Louvre in Bande à part, those abstract camera tricks diverting the viewer’s perspective, and Pierrot le Fou’s Pierrot-Ferdinand [Jean-Paul Belmondo] reading a paperback of Elie Faure’s Histoire de l’Art in the bath. Godard even aligns himself with the greatest painter of modern art, Picasso himself, positioning the profile of his creation, Pierrot le Fou, right in the middle of two Picasso portraits. Basically equal in size and perspective, it’s a statement: If Picasso is the greatest painter, then Godard is the greatest filmmaker. His constant deconstructions, reconstructions, edits and metaphors create a rich pop-art collage.

Following his passing earlier this year, we look at Godard’s obsessions with visual language through artworks in three of his most iconic films.

Pierrot le Fou, 1965

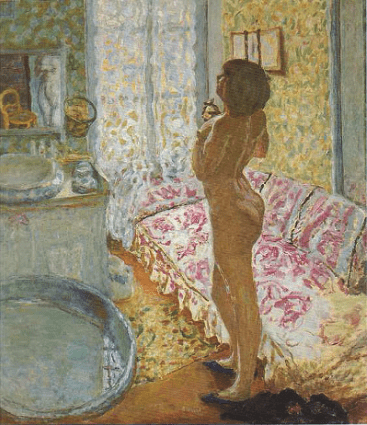

When talking about art in Godard’s work, Pierrot Le Fou is loaded with examples. The dense display of modernist artworks by Picasso, Modigliani, Chagall, Renoir and others appear in the form of posters and postcards, loosely taped on the walls, juxtaposed with random magazine covers of Paris Match, while our protagonists are seen to be avid readers of Elie Faure’s History of art. Dominated by blue, red and yellow, the pop art references are instant and continuous, albeit mixed with the classics. Pierrot’s blue painted face can be seen as a then-contemporary reference to Yves Klein, vanishing into the blue sea and the sky.

Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle, 1967

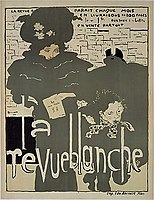

Between whisperings and bold typography Godard oscillates around social issues such as consumerism, prostitution and oppression. The latter is present with large billboards in shouty type on colour blocks, ordering us to take notice, buy this, see that, do this. In contrast, the whispering off-voice, with its hushed messages, is all too powerless against society at large. as individuals seem small, almost disappearing into the busy backdrop of colourful advertising. Throughout, Godard continues his obsession with graphic design and delivers a closer look at how present and powerful it really can be. From gas stations to cornflakes, everything has a written message for us in this world of typeface capitalism.

Deux ou trois choses que je sais d’elle, 1967

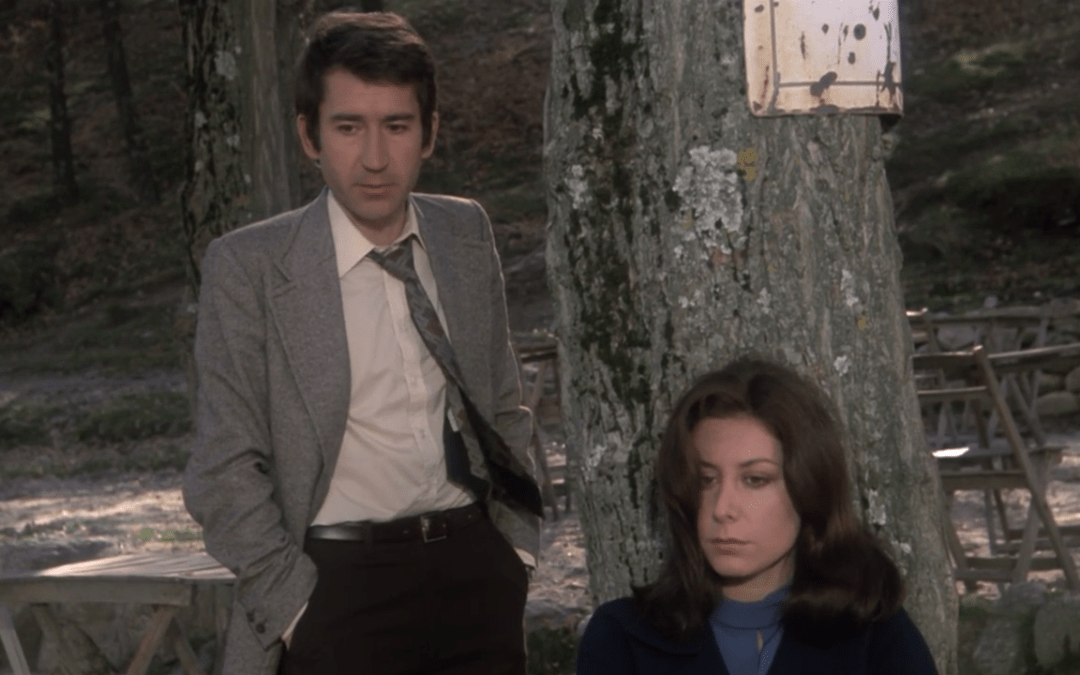

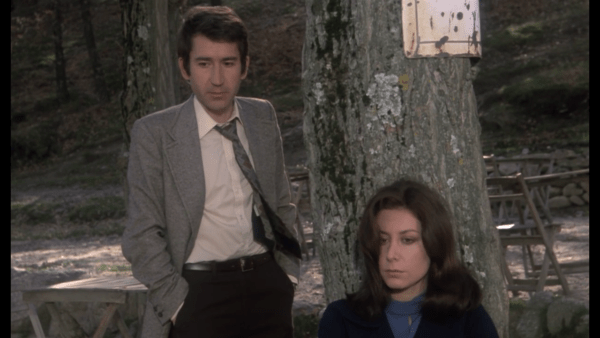

Masculin, Féminin, 1966

Title sequences and subtitles are underlined by the explosive noise of a gun while handwritten graffiti and printed newspapers structure this loose story of a young rebel in love. A hymn to pop culture and the Parisian youth of the 60s, the film is carried by Yeye music and features appearances from French stars Françoise Hardy and Brigitte Bardot. The font of those titles, with its typical oversized round dots, became symbolic of the French Nouvelle Vague as well as text boxes with unnaturally large word spacings. As an amateur graphic designer and autodidact, Godard’s layouts are synonymous with his art.

Godard’s fragmented narrative, cultural references and wordplay are reflected in the organisation of Masculin, Féminin. Described as a film about “the children of Marx and Coca-Cola”, Godard tells the story of their lives – ironically, the movie was censored in France for anyone under eighteen, exactly the group of people it was made for.

10 películas que influenciaron el cine de Jean-Luc Godard

https://moreliafilmfest.com/10-peliculas-que-influenciaron-el-cine-de-jean-luc-godard

Considerado uno de los grandes exponentes de la cinematografía, Jean-Luc Godard ha construido un universo de imágenes que, además de su bagaje previo como crítico de cine, ha retomado aspectos fundamentales de otros creadores. El British Film Institute (BFI) publicó un listado de 10 películas que han influenciado el cine de Godard.

El hombre de la cámara (1929), de Dziga Vertov

Es difícil señalar las películas que influyeron en el trabajo posterior de Godard cuando empezó a distanciarse del medio y se concentró en la filosofía y la teoría marxista. Sin embargo, en 1968, cuando Godard y Jean-Pierre Gorin reunieron a un pequeño grupo de maoístas para formar el grupo Dziga Vertov, la influencia colectiva detrás de su actividad política fue más fácil de aislar.

Con el tiempo, Gorin declaró: “El nombre del grupo fue originalmente una broma, pero al mismo tiempo fue, por supuesto, un acto político estético”. Godard y Gorin sintieron que la estética de Vertov fue más revolucionaria que la de Sergei Eisenstein, pues la narrativa, el desarrollo del carácter y el realismo dramática fueron ideológicas. Gorin declaró: “Adoptamos el nombre de Vertov después de una cuidadosa reflexión. No queríamos la vulgaridad de la narrativa. Si hay caracteres, es burguesa.”. La estética de Vertov ayudó a dar forma a los cortos socialistas-idealistas que el grupo crearía a finales de los años 60, y la participación proactiva de Godard en la lucha de clases.

Orphée (1950), de Jean Cocteau

Orphée (1950), de Jean Cocteau

Hay un rumor que dice que cuando Godard llegó por primera vez a París exclamó: “Seré el Cocteau de la nueva generación”. Cierto o no, hay muchas pruebas por escrito y entrevistas con Godard en las que reconoce su profundo respeto por Jean Cocteau. Fotos de Cocteau en diferentes etapas de su vida se pueden observar a lo largo de King Lear, aunque el mejor lugar para encontrar esta influencia es en Alphaville (1965).

Godard, inspirado por Red Desert (1965) de Michelangelo Antonioni, inicialmente quería hacer una adaptación de I am legend de Richard Matheson, sin embargo, filtró diversos elementos del cine de género para crear una película mucho más alineada con Orphée, la actualización de Cocteau al mito de Orfeo. La búsqueda de Lemmy Caution por Harry Dickson en Alphaville es paralela a la búsqueda de Orphée por Cégeste en la película de Cocteau. Con el uso de la poesía de los dos protagonistas para vencer a sus enemigos, se alinea la inteligencia de ambos directores, una mezcla de crítica social y su creencia compartida en la capacidad del arte para iniciar un cambio.

Johnny Guitar (1954), de Nicholas Ray

Johnny Guitar (1954), de Nicholas Ray

En los 50, los críticos de Cahiers du Cinéma dirigieron su mirada a Hollywood, con Nicholas Ray, una innegable influencia en la Nouvelle Vague. Godard escribió su famosa reseña de Bitter Victory (1957): “El cine es Nicholas Ray”, una declaración que demuestra su admiración por un determinado tipo de cineasta disidente americano, así como su desdén por una nación incapaz de reconocer a los grandes artistas.

La influencia de Ray, aunque evidente en la obra de Godard, es difícil de aislar en sus películas; sin embargo, existen numerosas referencias a su trabajo. En Le Mépris (1963), el personaje de Michel Piccoli afirma haber escrito Bigger than Life (1956) de Ray, y en Pierrot le fou (1965), el personaje de Belmondo permite a su niñera ver por tercera vez Johnny Guitar porque “ella debe educarse por sí sola”. Se podría argumentar que el abrupto estilo de edición de Godard es en donde se observa la influencia de Ray, un argumento apoyado por la dedicación de Godard en Made in U.S.A. (1966), pues tanto Ray y Samuel Fuller “me enseñaron el respeto por la imagen y el sonido.”

Viaje a Italia (1954), de Roberto Rossellini

Viaje a Italia (1954), de Roberto Rossellini

Viaje a Italia de Roberto Rossellini fue muy admirado por los críticos de Cahiers du Cinéma, elogiando su capacidad para unir el clasicismo cinematográfico con la autenticidad confesional de la realización de documentales. Godard estaba particularmente impresionado por el estilo íntimo de la película: “Una vez que vi Viaje a Italia, sabía que, aunque nunca fuera a hacer películas, podría hacerlas”.

Godard y Rossellini tuvieron una relación tempestuosa y no estaban de acuerdo en diversas cuestiones. Rossellini fue supuestamente hostil hacia la cinefilia, y Godard dijo: “Me encanta el cine. Rossellini ya no lo ama, está separado de él”. Sin embargo, la influencia de Rossellini fue un factor importante en la obra de Godard a lo largo de los años 60, especialmente en su quinto largometraje, Les Carabiniers (1963), basado en la obra I carabinieri del dramaturgo italiano Beniamino Joppolo. Rossellini hizo una versión de la obra en 1962, pero enfrentando críticas hostiles y quejas de carabineros reales, la policía militar de Italia. Según el biógrafo de Rossellini, el guionista Jean Gruault grabó una cita de Rossellini narrando la obra y se la pasó a Godard.

La calle de la vergüenza (1956), de Kenji Mizoguchi

La calle de la vergüenza (1956), de Kenji Mizoguchi

La obra de Kenji Mizoguchi tiene poca similitud con la edición de la animada e imprescindible obra de Godard. A pesar de sus diferencias estilísticas, ambos fueron atraídos hacia temas similares, por los que sus películas eran políticas y a menudo interesadas por la situación de las mujeres. El crítico francés Jean Douchet dijo una vez: “Vivre sa vie habría sido imposible sin La calle de la vergüenza, la última y más sublime película de Mizoguchi”.

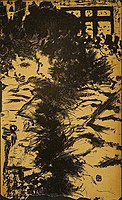

Mizoguchi utilizó el cine para crear atmósferas, dando al espectador un portal dentro de la propia película. Es esta transformación de estilo que hizo un llamado estilístico a Godard. La preferencia de Mizoguchi por los tiros de grúa durante las escenas de violencia dio a la cámara una presencia inquietante, que permite al público observar desde la distancia y así, dar un testimonio de la crueldad mecánica de la inhumanidad en la pantalla. El estilo de Mizoguchi permitió a Godard imponer un enorme efecto de distanciamiento de Bertolt Brecht (Verfremdungseffekt), sobre todo en la famosa escena de Weekend (1967), una secuencia de siete minutos destinados a sacudir al espectador pasivo hacia una confrontación con la brutalidad de la sociedad de consumo.

Forty guns (1957), de Sam Fuller

Forty guns (1957), de Sam Fuller

Durante una escena de la fiesta en Pierrot le fou, el personaje de Jean-Paul Belmondo pregunta a Sam Fuller: “¿Qué es el cine?”, y él responde: “El cine es como un campo de batalla: amor, odio, acción, muerte… una palabra: emoción”. La respuesta de Fuller conmovió a Godard. Fuller, que no sólo dirigió sino que escribió y produjo sus propias películas, fue otro de los directores americanos que Godard defendió en las páginas de Cahiers du Cinéma, admirando su cine brutal, político y pesimista.

Godard asimiló el estilo cinematográfico de Fuller, su diálogo sostenido, los primeros planos y la inventiva dentro de las limitaciones del cine de género. Además, Godard pudo retomar el rifle de Eve Brent en Forty Guns para Breathless. El brusco e inteligente enfoque de cine de género de Fuller se convertiría en el escalón artístico entre el cine estadounidense que admiraba la Nouvelle Vague y el enfoque de cine posmoderno que Godard desarrollaría más tarde.

Pickpocket (1959), de Robert Bresson

Pickpocket (1959), de Robert Bresson

En su top 10 para Cahiers du Cinéma de 1959, Godard colocó a Pickpocket (filmada en las calles de París al mismo tiempo que él filmó Breathless) como la mejor película del año. A pesar de que el cine espiritual de Bresson es opuesto a las creencias seculares de Godard, su influencia sobre Godard fue profunda y duradera. Aunque el director francés afirma que Pickpocket fue la principal inspiración para Le petit soldat(1963), la influencia de Bresson es quizá más evidente en Vivre sa vie (1962), el trágico retrato de Godard de una vida contada en 12 escenas creadas para mostrar en lugar de explicar la difícil situación de su joven protagonista. Este intento de ‘objetividad’ cinematográfica no es diferente a lo que se ve en Pickpocket, en donde la austera narración de Bresson sólo muestra lo que es necesario para obtener un punto de vista ‘objetivo’.

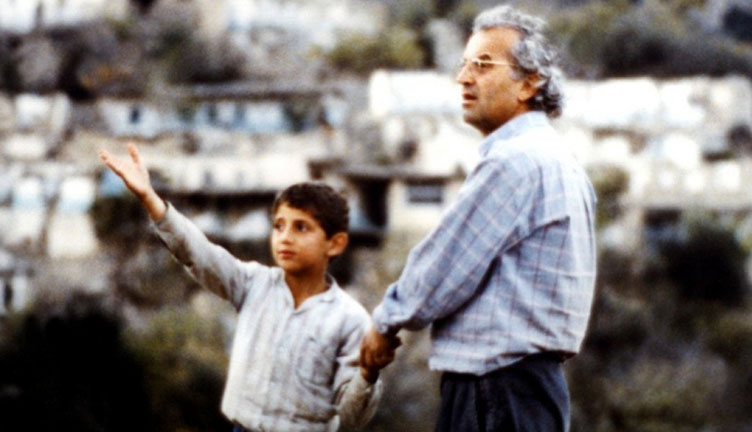

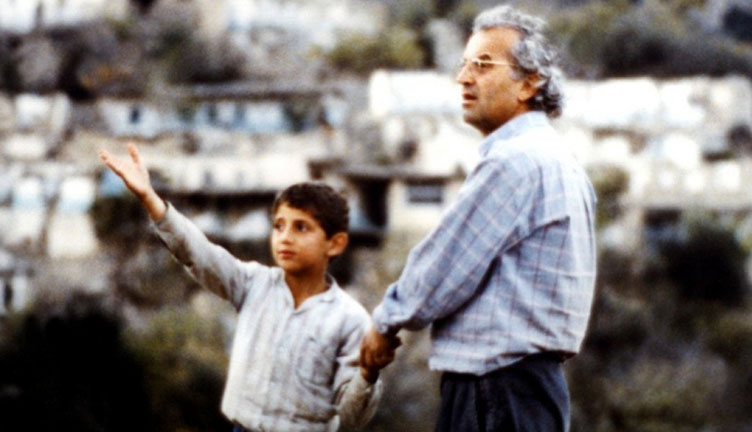

Life, and Nothing More… (1992), de Abbas Kiarostami

Life, and Nothing More… (1992), de Abbas Kiarostami

Godard dijo: “El cine comienza con D. Griffith y termina con Abbas Kiarostami”. Hay elementos de los trabajos anteriores de Kiarostami que claramente conforman el periodo posterior de Godard, en particular su película de 2004, el ensayo poético Notre musique. Life, and Nothing More… obliga al público a explotar la línea entre la realidad y la ficción con el uso del documental y el docudrama, y por tanto, cuestionar la posición del autor mediante la inserción de un personaje de ficción como un sustituto de sí mismo.

Una influencia importante sobre Godard fue el ensayo de Bazin de 1945 The Ontology of the Photographic Image, con su idea de que todas las imágenes filmadas son, por definición, la realidad filmada, definiendo gran parte de la obra de Godard. Este se convertiría en una inspiración mucho más rica para la yuxtaposición entre no ficción y ficción de su obra tardía, una manera de explicar su gran elogio por Life, and Nothing More…

La lista de Schindler (1993), de Steven Spielberg

La lista de Schindler (1993), de Steven Spielberg

En 1967, la secuencia final de la enigmática y audaz Weekend anunció el “Fin del cine”, y no sólo marca el fin del periodo narrativo y cinematográfico en la carrera de Godard, sino su rechazo de la industria en su conjunto. Es difícil establecer claramente las influencias en su obra más vanguardista; sin embargo, un punto muy publicitado en sus películas fue su ira por La lista de Schindler, de Steven Spielberg.

Cuando el Círculo de Críticos de Nueva York quiso homenajear a Godard en 1995, él se negó mandando una lista con nueve aspectos del cine estadounidense que fueron incapaces de influir en el cine. Lo primero en la lista fue el fracaso “para evitar que el Sr. Spielberg reconstruyera Auschwitz”. El fracaso del cine para prevenir o registrar los campos de concentración han sido una de las principales preocupaciones de Godard y uno de los temas principales en Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988) y en Eloge de l’amour (2001). Godard consideró la reconstrucción de los campos de concentración el motivo de la narración una obscenidad y se esforzó por corregirlo con su trabajo.

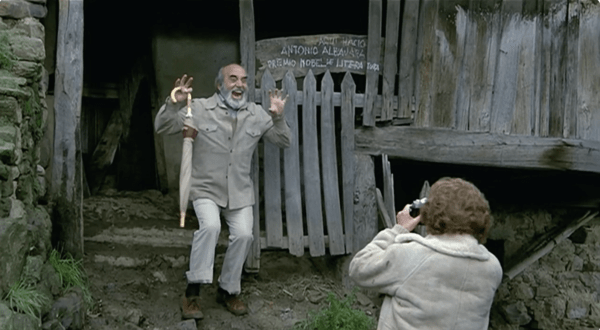

From Caligari to Hitler: German Cinema in the Age of the Masses (2014), de Ruediger Suchsland

From Caligari to Hitler: German Cinema in the Age of the Masses (2014), de Ruediger Suchsland

Hay una gran probabilidad de que Godard aún no haya visto la adaptación de 2014 de Rüdger Suchsland al libro del influyente sociólogo Siegfried Kracauer, From Caligari to Hitler, el material de origen para Germany Year 90 Nine Zero (1991), y la clave para entender la fascinación de Godard con la interacción entre el cine y la historia.

Parte narrativa, parte ensayo, sobre la historia y la política alemana, Germany Year 90 Nine Zero, establece los paralelismos entre la caída del muro de Berlín y la era Weimar en Alemania. En el acto final de la película, The Decline of the West, Godard inserta clips del cine de la era de Weimar. Las escenas de Fritz Lang en The Testament of Dr. Mabuse (1933), señalados en el libro de Krakauer, unían el cine expresionista con la llegada del régimen nazi. Godard no replica el análisis de Krakauer en su totalidad, pero utiliza películas de la década de 1920 para entender la situación incierta de Alemania después de la caída del muro. La idea de que el cine persigue la periferia de nuestra historia colectiva, silenciosamente documentada e intuida por nuestra vida, es una tema que prevalecerá en todo el trabajo posterior de Godard.

Orphée (1950), de Jean Cocteau

Orphée (1950), de Jean Cocteau Johnny Guitar (1954), de Nicholas Ray

Johnny Guitar (1954), de Nicholas Ray Viaje a Italia (1954), de Roberto Rossellini

Viaje a Italia (1954), de Roberto Rossellini La calle de la vergüenza (1956), de Kenji Mizoguchi

La calle de la vergüenza (1956), de Kenji Mizoguchi Forty guns (1957), de Sam Fuller

Forty guns (1957), de Sam Fuller Pickpocket (1959), de Robert Bresson

Pickpocket (1959), de Robert Bresson Life, and Nothing More… (1992), de Abbas Kiarostami

Life, and Nothing More… (1992), de Abbas Kiarostami La lista de Schindler (1993), de Steven Spielberg

La lista de Schindler (1993), de Steven Spielberg From Caligari to Hitler: German Cinema in the Age of the Masses (2014), de Ruediger Suchsland

From Caligari to Hitler: German Cinema in the Age of the Masses (2014), de Ruediger Suchsland